|

| Longfellow's Minnehana, dying poetically and clothed more or less as nature made her |

In the 2016 American League playoff series, the Toronto Blue Jays faced the Cleveland Indians. Inevitably, a Canadian aboriginal activist appealed to the Canadian and Ontario Human Rights commissions to prohibit use of the visitor’s team name in Canada. Nor were they to to wear their uniforms, display their logo, or show their mascot. All were offensive to First Nations.

In support of the proposed ban, a “meme” hustled around the Internet holding that Indians as a team name was offensive just as it would be offensive to call a team "The New York Jews," or "The San Francisco Chinamen." So why should “The Cleveland Indians” be different?

Why, indeed? And why indeed is it different from the Minnesota Vikings, the Boston Celtics, the New York Knicks, the New York Yankees, the Montreal Canadiens, the Vancouver Canucks, or the Notre Dame Fighting Irish?

Teams everywhere want to name themselves after Indians. We have the Edmonton Eskimos, the Atlanta Braves, the Chicago Blackhawks, the Kansas City Chiefs, the Washington Redskins, the Florida State Seminoles, and so on. Even teams in Europe have used Indian names. The Exeter Chiefs play rugby. The Malmo Redhawks play hockey in Sweden. Yet nobody anywhere seems to have ever wanted to name a team after Jews or Chinese.

Pure business, folks. If you name a team the Indians, people like and want to support it. If you name a team the Jews or the Chinamen, people do not. You lose money.

In other words, there is a general popular prejudice against the Jews or Chinese, at least as athletes, but in favour of the Indians.

The surest proof that a group is not being discriminated against, is that it is used as the name of a sports team. People want to cheer it.

The Canadian aboriginal activist was not acting against discrimination. He was pulling rank.

This, of course, flies in the face of the common preconception. Every right thinker thinks Indians have been oppressed throughout history. Haven’t they always been discriminated against? Haven’t they been despised, spat upon, forced off their land, looked down upon as “bloodthirsty savages,” at least until recent, more enlightened times? Wasn’t the only good Indian once a dead Indian?

Nope. This is all a beautiful myth. As C.L. Sonnichsen puts it, not quite felicitously, “If the Apache is a gentleman of distinguished culture, the white man is a savage” (C.L. Sonnichsen, From Hopalong to Hud [College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1978], p. 65). He misuses the term “savage”--he means moral evil. If you believe in the myth of the “noble savage,” you must automatically believe that civilized man is evil. If the state of nature is a state of grace, it follows that all evil comes with civilization. The former assumption requires the latter. So it must be true that civilization is oppressive of the natural man. The Indian must have been hard done by.

Accordingly, without citing any actual evidence, the “TV Tropes” web site, for example, explains as given that “In the era of the ‘Revisionist Western,’ (the era in which we find ourselves) fiction often attempts to provide a more diverse and historically accurate view of violence by and against Native Americans.” The prior norm, then, was ahistorically anti-Indian.

“One of the main problems with the earlier Westerns,” explains a movie site, “is that they painted the Native Americans into the stereotypical savage who was only out to rape, pillage, and murder the white man “(Clay Upton, “Stereotyping Indians in Film,”

http://clioseye.sfasu.edu/Archives/Main%20Archives/Stereotyping%20Indians%20in%20Film%209Upton).htm).

If t’were so, t’were a grievous fault.

“Before the movies added sound,” this account continues, “the Native Americans in films were stereotyped. They were always shown with scowls, while wearing war paint, showing that they were ready to kill at any time, or that they were less than the whites and that the Indians had need to be helped with everything having to do with the white way of life” (ibid).

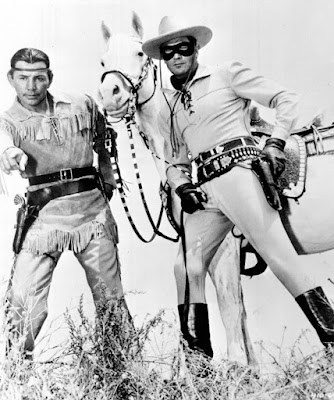

Hmm. But does that sound like Tonto as you remember him?

|

| At left: bloodthirsty savage. |

Didn’t we all grow up with the righteous Tonto, hearing about how Pocahontas saved the life of what’s-his-name—the European is a lesser player in the legend? How the Pilgrims and the friendly local Indians celebrated the first Thanksgiving? How the Indians showed the incompetent Europeans how to survive in this strange new world? How Sacajawea skillfully guided Lewis and Clark across the Northwest? How Tiger Lily, the Indian princess, was a true and loyal friend (and love interest) to Peter Pan?

How bloodthirsty was all that?

Has somebody here been smoking Jimson Weed?

There certainly seems to be a stereotype, but not the one claimed. A rather more noble one.

More sophisticated analyses go so far as to admit that there are two standard portraits of the North American aborigine: not just the “bloodthirsty savage,” but also the “noble savage.” Both, however, the wise will understand, are equally wrong. Lacy Cotton writes of “the swinging pendulum of popular opinion concerning American Natives, and how that opinion always reached for one extreme or the other” (Lacy Noel Cotton, “American Indian Stereotypes in Early Western Literature and the Lasting Influence on American Culture,” MA thesis, Baylor, 2008, p. 37).

That sounds terribly balanced and enlightened, doesn’t it?

However, it ought to count for something, and seems not to, that the “noble savage” is commonly the Indian encountered in fiction, whereas the so-called “bloodthirsty savage” is the one most often found in eyewitness accounts.

In other words, only one of them is a literary stereotype.

And it isn’t the prejudicial one.

The idea is that Western civilization, being evil and greedy, has invented a slander against the Indians in order to steal their land. Think of the villain Ratcliffe in Disney’s Pocahontas, digging the beach for gold.

Hence indeed the whole idea that the “whites” stole the Indian land. It must be so. It is a necessary part of the Edenic noble savage myth that somebody took Eden away. Along with the idea that the Indians were particularly connected to the land.

Never mind that the white settlers never had any practical need to steal land from the Indians, whose numbers had already been dramatically reduced by disease. Never mind that there is still adequate uncultivated land around Attawapiskat and any point north to continue the traditional Indian way of life, if anyone were mad enough to want to.

Hence the strange untrue assertion that in the past, our ancestors despised the Indians, but now, we are more enlightened. A rejection of “civilization” is a rejection of tradition. That is what civilization is. A rejection of tradition is a rejection of the supposed wisdom of our ancestors, in favour of the spontaneous desires of the present time. If savages are better off, civilization is evil. If civilization is evil, our civilized ancestors are evil, or their counsel is. We, on the other hand, being at least potentially in and of the moment, if we learn the trick of being here now, can make some personal claim to natural spontaneity and following our own instincts. We enlightened are on the side of the Indians.

Keats put it plainly in his romantic ballad, “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” The narrator’s fantasy of unrestricted romantic love is arrested by an interfering conscience personified as:

“pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;”

|

| Hughes, La Belle Dame Sans Merci |

The voices of social propriety—our ancestors—the dead.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gapèd wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

Some may object that the aboriginals themselves have and had a great respect for the wisdom of their ancestors. Indeed they did—they too, like most men everywhere, saw the critical value of civilization. They were themselves not romantics, and would have had no time for such mad ideas. But as a practical matter they were crippled in this by the lack of any form of writing. Their knowledge of their own traditions, and their ability to build on them, was limited to living memory.

|

| Indian princess |

Related as well to the noble savage archetype—indeed, its epitome--is the cult of the beautiful Indian princess: Pocahontas, Sacajawea, Tiger Lily, Leonard Cohen’s Kateri Tekakwitha, Land O’Lakes butter, and so on. The Indian princess is the Belle Dame Sans Merci, image of, in the end, free love. She is found also in Kore, Persephone, the innocent daughter of Mother Nature. She is the possibility of unbridled raw romantic passion, emotion without pale reason, including and symbolized by carnal union, without the restraints imposed by polite society. Adam and Eve before the fig leaves.

The weird legend that the residential schools were harmful to the Indian children also functions as part of the same myth: the schools were, symbolically, the imposition of evil civilization on these pure children of the forest, these Indian innocents and virginal maidens. The white man is Pluto, god of the underworld, rich, selfish, and cruel; the residential school is his kingdom of Hades, to which the virginal maiden is abducted.

In 1911, just as today, just as every day, everyone “knew” that the discovery of the nobility of savages was some recent revelation. In a 1911 copy of The Dallas Morning News, the Associated Press gives a favorable review of a book contemporary to its time, titled

The Indian Book by William John-Hopkins. AP praises the book for its “multi-layered view of the Mandan Indians,” stating that “the author makes the simple life of these primitive people vividly human, and the child forms a sympathetic and humane conception of this vanishing race, altogether different from his usual picture of the paint-daubed scalper” (Cotton, p. 41).

But this “usual picture” seems always to have been quite unusual. One could argue that the noble savage myth is even older than Persephone, is as old as the oldest sustained narrative known, The Epic of Gilgamesh: Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s BFF, is a wild man of the forests who comes to rescue mankind from, it seems, excessive governance.

To the Greeks, in turn, noble savagery evoked a lost “Golden Age.”

In the Golden Age, according to Hesiod, men

“lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief: miserable age rested not on them; but with legs and arms never failing they made merry with feasting beyond the reach of all devils. When they died, it was as though they were overcome with sleep, and they had all good things; for the fruitful earth unforced bare them fruit abundantly and without stint. They dwelt in ease and peace.”

In India, the

Mahabharata nurses the same cosmic fantasy:

“Men neither bought nor sold; there were no poor and no rich; there was no need to labour, because all that men required was obtained by the power of will; the chief virtue was the abandonment of all worldly desires. The Krita Yuga was without disease; there was no lessening with the years; there was no hatred or vanity, or evil thought whatsoever; no sorrow, no fear. All mankind could attain to supreme blessedness.”

The myth of the noble savage is every man’s yearning for a simpler life in the midst of the restraining requirements of existence with others. We each indulge it, spontaneously, when we feel nostalgia for our youth, a supposedly happier time. That’s how many of us remember childhood. But it is unlikely to be true of real history

|

| All of life was once a garden |

Alexander Pope wrote in his "Essay on Man" (1734):

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk or milky way;

Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n,

Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n;

Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd,

Some happier island in the wat'ry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold!

To be, contents his natural desire;

He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire:

But thinks, admitted to that equal sky,

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

This was the most famous take on the American Indian in all of English literature in the 18th century.

And here we plainly see the noble savage as the dominant view, well before the Romantics. While Pope, a Catholic, does understand the Indian as lacking important knowledge, the latter lives where “No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold! [shades of Pluto, of Disney’s Ratcliffe]/To be, contents his natural desire.”

|

| Crane: Persephone and Pluto |

This, unfortunately, we know from missionary accounts to be untrue: Mr. Indian was very much tormented by fiends, and very much valued trinkets. But it fits with the Garden of Eden myth of a Golden Age of man.

It also reveals, properly enough, how very patronizing and condescending the “noble savage” idea really is towards Indians. Innocence is not itself a virtue, any more than ignorance is. It is simply a state of never having exercised free will.

On the French side, importantly for Canadian perceptions, there is Rousseau, also of the 18th century, the great proponent of the state of nature, and before him Montaigne. “He [Rousseau] explained that all men when in the state of nature were essentially good, with untainted intuitions and inclinations. But to be civilized was to be corrupted and made unhappy by experiences in society. Gaining knowledge through tuitions enforced unnatural behavior on the natural man and removed him from his more natural, and therefore good, inclinations.” “American Indians, then, became an ultimate example of man uncorrupted and unfettered by civilization, a concept that countered the beliefs surrounding original sin and reinforced that all men were, at their core, good” (Lacy Cotton, op cit., p. 30).

One might add Freudianism to the noble savage mix. Civilization, according to Dr, Freud, represses our natural instincts, and repression of our natural instincts ultimately causes us to go mad. Therefore – free sex is a moral right. Civilization is the nexus of evil.

One can see the attractions to the argument, quite independent from its possible truthfulness. Everybody, in the abstract, would prefer to follow their first instincts if they could. The only problem is everyone else doing likewise.

Feminism, too, drinks deep of this traditional joy juice of the Kickapoo: all tradition, all established social norms, are of the evil patriarchy, aka Pluto, established to oppress women, who themselves represent unblemished nature. All Indian princesses, all of them. Therefore – free sex is a moral right. Civilization is the nexus of evil.

One can see again why church-run residential schools get targeted as the chief villain in the piece. They teach original sin! They deny our primordial innocence! They oppose free sex!

Now let us pass to the specifically North American tradition.

The Transcendentalists, American Romantics, of course embraced the idea of original innocence. “This could be related to Emerson’s encouragement to seek the Aboriginal Self in his essay ‘Self Reliance.’ This self supposedly existed inside all men and listened not to the tuitions taught by society, but to the natural instincts of the soul” (Cotton, op cit., p, 30).

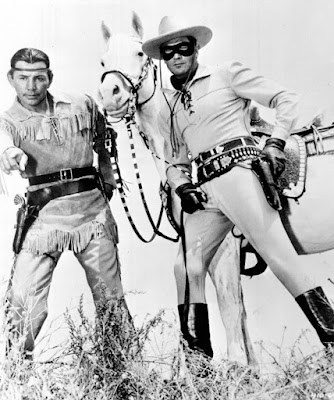

“The American Indian has since been idealized in this fashion throughout history,” notes Cotton, “and most notably in literature during the nineteenth century, including in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, with its noble descriptions of chief Chingachgook and his son Uncas, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, featuring Queequeg, and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, containing Crusoe‘s companion, Friday” (Cotton, op cit., p. 30). Not to mention Tonto, Chief Bromden in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Chief Dan George in Little Big Man, or Nobody in the recent Jarmusch film Dead Man.

|

| Queequeg |

In plain English, Indians have been traditionally venerated in the American, Canadian, and European mind, so long as that mind finds itself in a parlour. They are not now, and have never been, discriminated against; the discrimination has always been in their favour. While black Americans for many years wanted nothing so much as an end to segregation, and to fit in to the mainstream society, Indians saw the same proposal, offered to themselves, as an alarming loss of status.

So, no doubt, would the Queen of England.

If they have nevertheless been at times described as bloodthirsty savages, this can more easily explained not by prejudice, but by the fact that they were, at times, bloodthirsty savages.

Here are some European-invented “bloodthirsty savages” for you:

“Slowly the ship comes in, nearer and nearer the little wharf. Now, with a heavy swash of water and a boom, she touches; out jump her sailors to fasten her ropes.

But hark! what noise is that? It is the Indian war-whoop. And see! down rush the Indians themselves, yelling and brandishing their tomahawks. In an instant they have boarded the vessel. Down into the hold they go, yelling and whooping at every step.

The terrified sailors stand back aghast. Out they come again, lugging with them their heavy chests of tea.

Still they yell and whoop; and over go the chests into the dark water below.

And now, when every chest is gone, suddenly the Indians grow very quiet; they come off from the deck; and, orderly, take their stand upon the wharf; then do we see that they were not Indians at all. They were only men of Boston disguised.

This then was the Boston tea-party, which took place in Boston Harbor on the evening of December 16, 1773. (Pratt, Mara L., American History Stories, Volume II, 1908, pp. 30-31).

Many of us have heard the tale, of the first stirrings of the American War of Independence.

But did you ever wonder why the disaffected colonials dressed up as Indians?

For the same reason the Cleveland baseball club does.

Americans in general, and Canadians just as much, far from seeing the Indians as a despicable underclass of horrible others, have always wanted to identify themselves with them. The Europeans were the bad guys. As for we colonials, nobody here but us innocent, freedom-loving Indians.

Donald Grinde and Bruce Johansen, in their book, Exemplar of Liberty: Native America and the Evolution of Democracy, devote an entire chapter to analyzing why the Sons of Liberty used Mohawk disguise. “The Mohawk image,” they conclude, “was emerging as a revolutionary symbol of liberty in the new land, long before Uncle Sam came along. The resort to Indian guise was not seen only in Boston, but at similar protests up and down the Atlantic coast. One unit of the Sons of Liberty called themselves the ‘Mohawk River Indians.’” Mock Indians burned the British ship Gaspee in June of 1772. Some anti-British proclamations distributed by the patriotic groups were signed “The Mohawks.” (Grinde, Donald A.; Johansen, Bruce E [1991]

Exemplar of Liberty: Native America and the Evolution of Democracy).

|

| Bloodthirsty savages |

Notice the eagle on the Great Seal of the United States—arguably an Indian symbol. And note the arrows he holds in his left talon. Is it Indian inspired? I don’t know: flip a coin. Wait—isn’t that an old Indian-head penny? No, my mistake. It’s an Indian-head nickel.

In October 1988, the U.S. Congress passed Concurrent Resolution 331, to formally recognize the influence of the Iroquois Constitution (the Great Law of Peace) upon the American Constitution and Bill of Rights. This seems highly dubious; if you actually read accounts of the (oral) Iroquois Constitution, it is hard to find anything in it that resembles the US Constitution. But it seems to be something everyone wants to believe. It makes Americans, symbolically, the descendants of the Indians.

Hence, symbolically, American “freedom,” freedom from the commands of Keats’ pale kings and princes, from the baggage of the “Old World.” The British are the oppressive Europeans, the Americans the free and brave Indians.

Canadians, of course, traditionally disagree. Americans north of 49 are the oppressive Europeans. Canadians are the true successors to the Indians. Were we not the allies of Tecumseh and Joseph Brant? Did we not give sanctuary to Sitting Bull? If we live in the West, do we not consider Louis Riel our spiritual father? If we live in the Quebec, did we not grow up with tales of the lovely Indian maiden Kateri Tekakwitha?

|

| Devotional image of St. Kateri Tekakwitha |

There are two great American founding myths. Both intimately involve native people. One is the story of the first Thanksgiving, of union and amity between the new settlers and the native people, the natives passing on their wisdom. The other is the story of Pocahontas.

Here it is from a nineteenth-century children’s history book:

“Two large stones were placed in front of Powhatan and Smith was pinioned, dragged to the stones, and his head placed upon them, while the warriors who were to carry out the sentence brandished their clubs for the fatal blow. One of the daughters of Powhatan, named Matoa, or Pocahontas, sixteen or eighteen years old, sprang from her father's side, clasped Smith in her arms, and laid her head upon his. Powhatan, savage as he was, and full of anger against the English, melted at the sight. He ordered that the prisoner should be released, and sent him with a message of friendship to Jamestown. (Mann, Henry, The Land We Live In: The Story of Our Country, 1896).

And from the early twentieth century:

“A few days afterward, Captain Smith was brought before Powhatan and his braves. A big stone was brought and laid on the ground in the chief's wigwam. Powhatan again sat on his throne of furs, and his warriors stood round in a circle. They looked fierce in their war paint. They were eager for the white man's death. The prisoner's arms were tied behind him. His head was laid on the stone. An Indian brave stood ready with his war club. The club was raised to strike. A scream was heard, and in rushed Pocahontas and threw herself on the captive.

‘Kill me,’ she cried, ‘kill me, but you shall not kill him.’

The Indian did not dare to strike. He would have killed his chief's beloved daughter. The heart of the Indian chief was touched. Of all his children, he loved her best.” (Blaisdell, Albert E., and Francis K. Ball, The Child's Book of American History, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company 1923 , p. 32-3).

There is slim evidence that the scene actually happened. But it is cherished, because it says something important about the natural man, or natural woman: that she is innately good, that her most basic instinct is love. Trouble only comes with growing up.

We want that to be true. It reflects well on all of us. The archetype of the Indian princess, the Pocahontas myth, represents this hope.

Ever since, it has been a mark of nobility in Virginia to claim direct descent from Pocahontas. Charles Dudley Warner, writing in 1881, speaks of "the natural pride of the descendants of this dusky princess who have been ennobled by the smallest rivulet of her red blood" (The Story of Pocahantas). Two American first ladies have claimed such descent: Edith (Woodrow) Wilson and Nancy Reagan.

In North America, in short, to be Indian is to be nobility. Johnny Cash and Jessica Alba were publicly disappointed to discover they had no Indian blood, contrary to their family traditions. Elvis always insisted he did.

In Canada, this eternal desire to assume Indian identity is well-represented recently by John Ralston Saul’s essays arguing that Canada is ultimately a “Metis nation.” “Canada’s founding rationale and ongoing purpose in the world is to serve as a bulwark against the American steamroller of technology, capitalism and individualism” (Andrew Potter, “Are We a Metis Nation?” Literary Review of Canada, April, 2009). We hosers are the noble savages; the Americans represent the evils of plutocratic civilization. Saul argues that the “single greatest failure of the Canadian experiment, so far, has been our inability to normalize—that is, to internalize consciously— the First Nations as the senior founding pillar of our civilization.” To Saul, “single-payer health care, environmental protectionism, peacekeeping, soft power diplomacy, even the egalitarian elements of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms—these all supposedly bear the unmistakable stamp of aboriginal ideas and influences.” All the great virtues of the Canadian personality are owed to the country’s Métis character, and so our “desire for harmony and balance, our preference for diversity, inclusion and complexity, our renewed interest in egalitarianism—all are emanations of our aboriginal soul” (LRC).

Remarkable how like the Americans we are in our founding myth. Odd that we evolved to so many opposite conclusions about our Indian heritage. To Americans, being Indian means rugged individualism and personal freedom. To Saul, it means communitarianism, keeping everyone equal, and individualism is from the polluting civilization.

Put an Indian face on it, and any ideology at all sounds more plausible.

|

| Sacagawea intrepidly guiding Lewis and Clark |

Sacagawea is the second great American historical myth of the aboriginal princess. She gets to be on the dollar coin, after all – rather like the Queen in Canada. Although she is of course not the first Indian to feature on the coinage. She is commonly credited with guiding Lewis and Clark to the Pacific.

This is almost certainly not true. According to the expedition’s records, she gave directions in only a few instances. Her principal value to the expedition was probably her mere presence, because it suggested to the various native groups the peaceful intent of the expedition.

Nevertheless, her part has been lionized and widely commemorated because it fits with the desired American archetype of the good-hearted and wise Indian princess, especially as a founder figure.

The myth has continued to play out throughout American literature.

The first really popular American novel had an Indian in its title: James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans, 1826. And the eponymous Indian was certainly of the noble savage tribe—literally a noble in Indian terms, the son of a chief and last of his noble line.

"Uncas ... clearly demonstrates a noble and chivalrous nature toward Cora Munro, his unrequited love” writes William Starna. “He dies stoically and with honor at the hands of Magua after Cora is killed by another Huron" (William A. Starna, “Cooper's Indians: A Critique,” [SUNY Oneonta] Originally published in James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art, Papers from the 1979 Conference at State University College of New York, Oneonta and Cooperstown. George A. Test, editor, pp. 63-76).

Nor is Last of the Mohicans Cooper’s only tale of a noble savage. “James Fenimore Cooper was well known,” writes Lacy Cotton, “for his sympathetic opinion of Native Americans in his writing” (op cit., p. 65).

“Cooper's The Pioneers (1823), ... is set in the twilight of rural 18th century central New York where the frontier has now moved West beyond them; the beautiful wilderness replaced by orderly farms. Cooper's ‘civilization,’ however, is prone to irrational, sinful destruction of nature. The townsfolk's slaughter of the wild animals is well beyond any safety or economic justification. In one scene, the hero character of Natty Bumppo, whose legendary wilderness skills and attitudes were honed through his intimate contact with nature and Indians, is appalled at their employment of a cannon to bring down a massive flock of migrating pigeons. Bumppo criticizes the ‘wasty ways’ of so-called civilization and says it's a sin to kill more than one can eat. Meanwhile, the noble Indians struggle to understand and accept the ‘order’ imposed on them in the form of strict hunting laws.”

Unlike his hero Natty Bumppo, Cooper had little intimate contact with nature or Indians. This no doubt helped his characterization immeasurably.

“Chingachgook is first introduced (in the arrangement of the book order) in The Deerslayer (1841) as Natty Bumppo‘s traveling companion and adopted brother. His presence is representative of nature, and natural living, and he is often contrasted against the actions of other white characters like Harry March. One of the most poignant scenes in the novel takes place in chapter thirty-two, where Natty Bumppo stands between two trails, that to the garrison, and that to the village of the Delawares. Waiting in one direction are Chingachgook and Hist-Oh!-Hist, and in the other, Judith, Captain Warley, and the settlement troops. Natty Bumppo is faced with the choice of moving on into the wilderness with the Indians or devoting himself to Judith and leading a domestic, civilized life with her. Ultimately, he chooses to go with Chingachgook and Hist-Oh!Hist, metaphorically rejecting white civilization and choosing the life of the Noble Savage for himself as well” (Cotton, p. 43-44).

This is the ultimate American road less travelled. The “Last Mohican” of the book title may not, in the end, be Uncas. For Natty Bumppo too is a Mohican. He is Uncas’s adopted uncle, brother of Chingachgook, and he has symbolically chosen the Indian way of life. The “Last of the Mohicans, the inheritor of the Indian ways, may as well be understood to be the American frontiersman. The cowboy.

The cowboy was never the enemy of the Indian. He was his cultural descendant and adopted brother. Both literary stock characters stood for a primitive freedom against encroaching settlement. Both must be understood, following the Eden convention, as people of the lost golden age, always riding off into the sunset, always the last of their kind, or even already extinct, beings of a more wonderful past. The Old West is almost dead, and it always was. Innocence by its nature, like virginity, like childhood, must be under dire threat. We grow up. Damn.

The noble savage has remained at the noble and savage heart of American literature. In 1826, actor Edwin Forrest took out an advertisement in the

New York Critic newspaper offering $500 “to the author of the best tragedy, in five acts, of which the hero … shall be an aboriginal of this country.” The winner was Metamora; or the Last of the Wampanoags. It became the first great American stage sensation.

Washington Irving was another loyal fan of the Noble Savage. In “The Trait of the Indian Character,” 1819-20, he wrote,

“The current opinion of the Indian character, …., is too apt to be formed from the miserable hordes which infest the frontiers and hang on the skirts of the settlements. These are too commonly composed of degenerate beings, corrupted and enfeebled by the vices of society without being benefited by its civilization…. Poverty, repining and hopeless poverty, a canker of the mind unknown in savage life, corrodes their spirits and blights every free and noble quality of their natures.”

Noble—nature. Note the inevitable juxtaposition.

“How different was their state,” he continues, “while yet the undisputed lords of the soil! Their wants were few, and the means of gratification within their reach. They saw everyone around them sharing the same lot, enduring the same hardships, feeding on the same aliments, arrayed in the same rude garments. No roof then rose but was open to the homeless stranger; no smoke curled among the trees but he was welcome to sit down by its fire and join the hunter in his repast. ‘For,’ says an old historian of New England, ‘their life is so void of care, and they are so loving also that they make use of those things they enjoy as common goods, and are therein so compassionate that rather than one should starve through want, they would starve all; thus they pass their time merrily, not regarding our pomp, but are better content with their own, which some men esteem so meanly of.’ Such were the Indians while in the pride and energy of their primitive natures they resembled those wild plants which thrive best in the shades of the forest but shrink from the hand of cultivation and perish beneath the influence of the sun.”

Cruel civilization crushes these innocent blossoms of the forest.

Note too that Irving presents this, in 1819, as the modern revisionist view of the Indians. Yet he is able to quote the same view already from an “old historian.” Being new is part of the myth, not the reality.

In a sense, however, Irving at least is right; the period before his own was dominated by the “captivity narrative,” which usually documented Indian cruelty to European captives. But there is a crucial difference: the authors of the original captivity narratives were writing from personal experience. Irving had little firsthand knowledge of actual Indians. His Indians were literary Indians, and literary Indians have always been noble savages.

|

| Longfellow's Minnehaha: Another Indian Princess |

To be fair, there was also a backlash to Irving’s and Cooper’s depiction of the native American. Some then still had experience of real Indians living outside the settled lands. This backlash was the far less well-remembered novel

Nick of the Woods, published in 1837 by Robert Bird. Its Indians were indeed more savage than noble, at least in the eyes of Bird’s protagonist. However, this was hardly an established motif of the time: rather, according to his preface, Bird wrote the book in rebuttal of Cooper.

“At the period when

Nick of the Woods was written,” Bird explains, “the genius of Chateaubriand and of Cooper had thrown a poetical illusion over the Indian character; and the red men were presented—almost stereotyped in the popular mind—as the embodiments of grand and tender sentiment—a new style of the beau-ideal—brave, gentle, loving, refined, honourable, romantic personages—nature's nobles, the chivalry of the forest.”

Bird was not trying to malign Indians, but simply to present a more realistic portrait. “It may be submitted that such are not the lineaments of the race—that they never were the lineaments of any race existing in an uncivilised state—indeed, could not be—and that such conceptions as Atala and Uncas are beautiful unrealities and fictions merely, as imaginary and contrary to nature as the shepherd swains of the old pastoral school of rhyme and romance; at all events, that one does not find beings of this class, or any thing in the slightest degree resembling them, among the tribes now known to travellers and legislators.”

“The Indian is doubtless a gentleman,” Bird allows; “but he is a gentleman who wears a very dirty shirt, and lives a very miserable life, having nothing to employ him or keep him alive except the pleasures of the chase and of the scalp-hunt—which we dignify with the name of war. The writer differed from his critical friends, and from many philanthropists, in believing the Indian to be capable—perfectly capable, where restraint assists the work of friendly instruction—of civilisation: the Choctaws and Cherokees, and the ancient Mexicans and Peruvians, prove it; but, in his natural barbaric state, he is a barbarian—and it is not possible he could be anything else. The purposes of the author, in his book, confined him to real Indians. He drew them as, in his judgment, they existed—and as, according to all observation, they still exist wherever not softened by cultivation,—ignorant, violent, debased, brutal; he drew them, too, as they appeared, and still appear, in war—or the scalp-hunt—when all the worst deformities of the savage temperament receive their strongest and fiercest development.”

Bird was quickly condemned for this assertion and this depiction at the time, and has been condemned for it ever since. This may be why he is far less well-remembered than Irving or Cooper. His preface goes on to say: “Having, therefore, no other, and certainly no worse, desire than to make his delineations in this regard as correct and true to nature as he could, it was with no little surprise he found himself taken to account by some of the critical gentry, on the charge of entertaining the inhumane design of influencing the passions of his countrymen against the remnant of an unfortunate race, with a view of excusing the wrongs done to it by the whites, if not of actually hastening the period of that ‘final destruction’ which it pleases so many men, against all probability, if not against all possibility, to predict as a certain future event.”

This idea of the Indian’s inevitable final disappearance, of course, has not happened: Bird, and not Cooper or Irving, has proven more prescient here. The idea of the inevitable passing of the Indian is, in the end, an aspect of the noble savage myth. Eden and the Golden Age, like childhood, must by their nature be lost forever in order to be truly romantic and real to the imagination; just as Swift’s Lilliput or Brobdingnag must not be found on any conventional charts. The noble savagists cannot, in the end, as Bird rightly saw, allow the Indian into the modern world. They must forever be picturesquely dying, or already dead.

Bird does not say that Indians are evil, but rather draws a fictional portrait of a man who does. A not-uncommon sentiment, Bird says, among those who had dealt with real wild Indians before the cruel influence of civilization blasted these innocent forest flowers. “No one conversant with the history of border affairs,” Bird writes, “can fail to recollect some one or more instances of solitary men, bereaved fathers or orphaned sons, the sole survivors, sometimes, of exterminated households, who remained only to devote themselves to lives of vengeance; and ‘Indian-hating’ (which implied the fullest indulgence of a rancorous animosity no blood could appease) was so far from being an uncommon passion in some particular districts, that it was thought to have infected, occasionally, persons, otherwise of good repute, who ranged the woods, intent on private adventures, which they were careful to conceal from the public eye.”

“The author remembers,” the author continues, “in the published journal of an old traveller … who visited the region of the upper Ohio towards the close of the last century, an observation on this subject, which made too deep an impression to be easily forgotten. It was stated, as the consequence of the Indian atrocities, that such were the extent and depth of the vindictive feeling throughout the community, that it was suspected in some cases to have reached men whose faith was opposed to warfare and bloodshed.”

Bird himself did not believe that Indians were in any way inferior or depraved. They simply behaved as their unfortunate condition, a war of all against all, required of them. It was the Romantics, he insisted, who saw Indians as inferior, as bestial.

Nevertheless, this seems to have been a rare and futile kick against the pricks already by the early nineteenth century.

Like the first widely popular play, the first musical score published in America was about Indians, and presented from the Indian perspective: “The Death Song of an Indian Chief,” released in March 1791 in the

Massachusetts Magazine (Cotton, op cit., p. 5).

It was always, after all, the proper business of Indians to be romantically dying.

“Romanticizing the Indian dominated western fiction and poetry between 1800 and 1830,” writes Cotton. “Titles such as

Frontier Maid; or, the Fall of Wyoming (1819);

Logan, an Indian Tale (1821);

The Land of Powhatten (1821); and

Ontwa, Son of the Forest (1822), all portrayed dramatically idealized Indians that fit into the Noble Savage definition. …. By 1830 the theater was dominated by ‘Indian’ plays, that heavily featured the Noble Savage motif. … [O]n stage in 1893 was Belasco and Fyles‘s play, ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me,’ which victimized innocent Indians at the hands of corrupt white culture” (Cotton, p. 6). Or rather, portrayed Indians as victimized at the hands of corrupt white culture.

So too among Canadian writers. Adam Kidd, in 1830 Montreal, wrote the long poem, “The Huron Chief,” featuring the lines

Undisturbed as the wild deer that strays o’er the mountain,

Or lily that sleeps in its calm liquid bed,

In that arbour of green, by the gush of the fountain,

Oft, oft has my Huron there pillowed his head.

But the hand of the white man has brought desolation —

Duncan Campbell Scott, Confederation poet, is often criticized for showing traditional Indian life as difficult; he was with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and knew something of real Indians. Nevertheless, his poetry shows the marks of the Noble Savage myth. In “On the Way to the Mission,” he tells the story of a lone Indian shot dead by Europeans, the “whitemen servants of greed,” in order to steal his sled-load of furs.

|

| Pauline Johnson recites |

And then there are Grey Owl, Pauline Johnson, and Emily Carr, aka “Klee Wyck.” Johnson claimed to be a native princess, and recited in Indian dress. Farley Mowat made his literary reputation with

People of the Deer (1952), about the Inuit. It was sympathetic to the native people, highly critical of the government, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Western civilization generally. “It’s the story,” explains Craig MacBride in the Toronto Review of Books, “of white people disrupting and ruining Indigenous culture” (March 15, 2013). Marketable. Unfortunately, there are charges that Mowat made most of his stuff up.

In Canada, claiming to be Indian or an adopted Indian has plainly always been a good career move in the arts.

Throughout the nineteenth, and into the twentieth, centuries, one of the most popular forms of entertainment throughout North America was the Indian medicine show. Indians, again, were shown to the rubes in a completely favourable light. The success of the enterprise depended, after all, on the general prejudice that Indians could not tell a lie. Accordingly, if they said a patent nostrum worked, it must work. “The Noble Savage‘s determining features,” notes Cotton in another context, “included a harmony with nature coupled with a moral innocence and inability to lie” (Cotton, p. 30).

We see the same prejudice in the naive acceptance by the Canadian courts of Indian “oral tradition” as of equal weight with written and signed treaties. We see it in the acceptance of “victim” statements without any further corroborating evidence by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. If an Indian says it, it must be true.

Were little white children once taught to see the Indians as bloodthirsty savages? Here is how an Ontario school history book of 1879 introduces them: "They were bold and cunning, generous to their friends, but bitterly revengeful to their foes. There were, however, some great chiefs among them, who were noted for their love of the people, their honesty, and their kindness to enemies (Jeffers, J. Frith,

History of Canada, 1879, p, 4). Said chiefs are not identified; we are left to speculate.

Of course, Canadian kids did once play that notoriously racist old game of cowboys and Indians. But consider: in order for it to work, roughly half of the kids must always have wanted to be Indians.

Nor were literary cowboys and Indians enemies by nature: they were brothers, like Uncas and Natty Bumppo, like Tonto and the Lone Ranger. If cowboys sometimes fought with Indians, this was the Indian way. Just as cowboys fought with cowboys, in their shoot-outs, and Indians fought with Indians, the Iroquois with the Huron, the Cree with the Blackfoot, the Huron with the Mohicans. It was the inevitable logic of life beyond police patrol and government control, and it was, in fictional form, as fun as any Tom and Jerry cartoon. The cowboy was the European Indian—the free man, the wanderer, living by his own code of honour outside the law.

The traditional image of the cowboy, and the original Western, began with dime novels in the second half of the 19th century. And the dime novels themselves began with tales of Indians. Only later did the cowboy emerge as a subject of similar interest to the same readership.

The first dime novel ever was

Malaeska, the Indian Wife of a White Hunter (1860). Its vision of Indian life, as first presented to the reader, is plainly romantic:

“wigwams might be seen through a vista in the wood. One or two were built even on the edge of the clearing; the grass was much trampled around them, and three or four half-naked Indian children lay rolling upon it, laughing, shouting, and flinging up their limbs in the pleasant morning air. One young Indian woman was also frolicking among them, tossing an infant in her arms, caroling and playing with it. Her laugh was musical as a bird song, and as she darted to and fro, now into the forest and then out into the sunshine, her long hair glowed like the wing of a raven, and her motion was graceful as an untamed gazelle. They could see that the child, too, was very beautiful, even from the distance” (p. 10).

Like an untamed gazelle: Malaeska is the familiar archetype of the innocent and good-hearted Indian princess, representing an imagined purity of nature. “[H]er untutored heart, rich in its natural affections, had no aim, no object, but what centered in the love she bore her white husband. The feelings which in civilized life are scattered over a thousand objects, were, in her bosom, centered in one single being; he supplied the place of all the high aspirations – of all the passions and sentiments which are fostered into strength by society” (p. 31-32). Pure of heart, in other words; here as the story progresses ruined by contact with the evil Europeans and their civilized prejudices.

The same motif is soon reprised in

The Frontier Angel (1861), its topic an Indian maiden’s “suffering and devotion.” This was followed in turn by

King Barnaby or The Maidens of the Forest: A Romance of the Micmacs (1861).

Oonomoo the Huron came in 1862, plus a romance,

Ahmo’s Plot, or The Governor’s Indian Child, based on the premise that Count Frontenac took an Indian wife, the daughter, of course, of a chief.

Laughing Eyes, in 1863, reverses the stock situation; it has a European maiden falling in love with an Indian prince.

Mahaska, the Indian Princess tells the continuing story of Frontenac’s supposed half-Indian daughter, her mother having died “of a broken heart, as we see forest birds perish in their cages.”

Obviously, the fallout from the residential schools was not the first time we conceived the idea that exposure to European civilization was harmful to native people.

The Indian Princess was soon succeeded, logically enough, by

The Indian Queen, purportedly the story of Mahaska become the Queen of the Senecas. In 1869,

Border Avengers, or The White Prophetess of the Delawares, announced an upcoming series on Wenona, the Giant Chief of St. Regis, including

Silent Slayer, or The Maid of Montreal, and

Despard the Spy, or the Fall of Montreal. Despard, a European, was the villain. Wenona, of course, a Mohawk, was the hero.

Over time, the frontier of romance, to remain plausible, had to move west.

The Lone Chief or the Trappers of the Saskatchewan (1873) tells of Chief Blackbird. It is a tale that “awakens our warmest admiration”; its heroine is a “strangely beautiful” Cree girl. This was quickly followed by

Old Bear Paw the Trapper King, or The Love of a Blackfoot Queen.

Indian princesses everywhere populated the West. Virginally.

|

| Buck Taylor |

In 1887, Henry Nash Smith, Beadle Dime Novels editor, hit upon the idea of the cowboy hero to add to the now-traditional Indian. He published a fictionalized biography of the real star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, Buck Taylor (William Levi Taylor). The literary Taylor, the original cowboy, reveals his true lineage in his origin story: he is first captured by the Comanches, then eventually freed by an Indian friend. It is like a second birth, as an adopted Indian, in the mold of Natty Bumppo.

And the cowboy, in turn, is the essential image, at home and abroad, of the American character. He is the American hero.

The Wild West Show as popular entertainment followed more or less the same evolution: the first Wild West shows, organized by artist George Catlin to tour the US and Europe, featured only Indians. Buffalo Bill Cody hit upon the idea of adding “cowboys,” Europeans who lived on the frontier and adopted many of the Indian ways, to the shows. While the Indians were spectacle enough in themselves, by doing this, he could add displays of trick shooting, horsemanship, roping, and other talents more easily found among the pool of European-Americans. Visiting Europe, the “cowboys” made a point of sleeping outdoors, like the Indian performers. They were, after all, children of nature.

In novels, the Western genre truly came into its own with the full-length yarns of Zane Grey. And, like his predecessors, Grey was a faithful acolyte of the noble savage. "His respectful treatment of Indians,” boasts the Zane Grey West Society web page, “was ahead of its time."

Yep. Always was, always is.

Among other treatments, Grey wrote The Vanishing American, obviously sympathetic to the eternally dying Indians.

“In his 1910 novel, Heritage of the Desert,” similarly, “Grey idealizes the Navajo people, particularly the Chief Eschtah” (Cotton, p. 47).

“This pattern of victimizing [sic] the Noble Savage continues in Grey’s novel, The Rainbow Trail (1915). In this story, yet another female Indian named Glen Naspa is seduced and assaulted by a white missionary” (Cotton, p. 48). The Vanishing American, similarly, features “lecherous and greedy ministers” who “oppose noble and good Indians that honor the nation by participating in World War I” (Cotton, p. 51).

Sound familiar? The missionary is the inevitable fall guy in the noble savage myth, because he introduces the idea of original sin.

In the same novel, “Shefford... discovers [an] Indian woman in her home, having died in childbirth, and his guilt over the tragedy leads him to feel something of the white man’s burden of crime toward the Indian weighing upon his soul.” “Grey,” Cotton adds, “was not the only author to use this method of victimizing [sic] an Indian woman and orchestrating her death as a metaphor for the ruthless cruelty of white culture” (Cotton, p. 49).

“The roots of this imagery,” Cotton goes on, “can be traced back as far as the 1890s, when David Belasco and Franklin Fyles wrote the play “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” This story of an Indian uprising involves a maiden named Fawn Afraid, whose involvement with white culture ultimately leads to her death” (Cotton, p. 49).

“Fawn Afraid”? You have to love it.

But Cotton is significantly wrong here. The imagery of the innocent Indian maiden being destroyed by contact with white culture is not from some play in the nineteenth century. It is an essential element of the Indian princess myth, going back to Greek mythology and Kore/Persephone. We have already seen it many times.

The popularity of the cowboy novel has, of course, spread beyond North America. When the Americans occupied Germany at the end of World War II, they were amused to find the Germans entirely wrapped up in the romance of the old frontier—as they largely remain today.

This is mostly due to Karl May, probably the most popular novelist in the German language, who specialized in “Western” stories.

But note that on May’s frontier, as in the early dime novels, the central hero is an Indian, not a cowboy: Minnetou, the “wise chief of the Apaches.” “Old Shatterhand,” the cowboy figure, is like Bumppo or the Lone Ranger his “blood brother.”

According to Anthony Grafton, writing in the New Republic, May always depicted Native Americans as “innocent victims of white law-breakers.” He had much that was unflattering to say about Jews, the Irish, the Chinese, blacks, and Armenians; but never about Native Americans.

Why were Indians special? “His readers longed to escape from an industrialized capitalist society,” writes Grafton, “an escape which May offered” (Grafton, “Mein Buch,” The New Republic, December, 2008). The noble savage, exactly.

Grafton points out that Karl May and his Western adventures were special favourites of Adolf Hitler. “Hitler later recommended the books to his generals and had special editions distributed to soldiers at the front, praising Winnetou as an example of ‘tactical finesse and circumspection’" (Grafton, op cit.). “The fate of Native Americans in the United States was used during the world wars for anti-American propaganda,” writes Frederic Morton in the New York Times. “The National Socialists in particular tried to use May's popularity and his work for their purposes” (Morton, Tales Of The Grand Teutons: Karl May Among The Indians. The New York Times, 4 January 1987).

This should not surprise us. The cult of the noble savage always had Nazi-esque overtones. Like Nazism, it was a cult of nature and the natural man. Like Nazism, it believed in a mystic oneness of the “volk” with the ancestral land and the landscape. Foreigners were not welcome. Like the Nazis, it believed in the value of racial and cultural “purity.” The evil forces of “cosmopolitanism” were simply transferred by the Nazis from May’s encroaching European plutocrats to the capitalist, cosmopolitan Jews.

But what about the movies? What about Hollywood? Surely here, at least, the racist stereotype of the bloodthirsty Indian descending on the helpless wagon train ruled supreme? As we have read, “One of the main problems with the earlier Westerns is that they painted the Native Americans into the stereotypical savage who was only out to rape, pillage, and murder the white man” (Clay Upton,

Stereotyping Indians in Film, http://clioseye.sfasu.edu/Archives/Main%20Archives/Stereotyping%20Indians%20in%20Film%20(Upton).htm). Up until “Little Big Man,” or “Dances With Wolves,” wasn’t the story always at the very least told from the point of view of the white man?

Anyone is free to believe that. So long as they have never seen a Western.

The very first Western movie with a narrative that featured Indians is told from the supposed Indian perspective: "The Red Man's View," 1909, by D.W. Griffith. According to a review of the day, the film is about "the helpless Indian race as it has been forced to recede before the advancing white, ... full of poetic sentiment" (NY Mirror, Thomas Cripps,

Hollywood's High Noon: Moviemaking and Society Before Television, JHU Press, 1997, p. 27).

If the reader doubts the accuracy of this characterization, he is advised that the full film is available for view at the Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/TheRedMansView_201401

Make no mistake: white people are the villains, and D.W. Griffith is rarely ambiguous about such things. They repeatedly drive the Indians off their land and, of course, abduct a poor defenseless Indian princess.

|

| Pocahontas, 1910 |

A classic treatment of the prototypical Pocahontas appeared in 1910, and a second version in 1911. In 1912 came “The Heart of an Indian Maiden” (YouTube:

https://youtu.be/-kVKKEEiJR0) and “The Invaders”-- said invaders, of course, being the Europeans. In the latter movie, according to IMDB, "the U.S. Army and the Indians sign a peace treaty. However, a group of surveyors trespass on the Indians' land and violate the treaty. The army refuses to listen to the Indians' complaints, and the surveyors are killed by the Indians."

Also in 1912 came “A Temporary Truce”: “three malicious drunks have just killed an Indian, solely to amuse themselves. When Jim abducts the prospector's wife, and takes her to a remote place, he soon afterwards encounters a party of angry braves seeking revenge" (IMDB).

Yes, you see fights between cowboys and Indians—but the cowboys are always to blame.

D.W. Griffith’s “The Battle of Elderbush Gulch” (1913) (Internet Archive,

https://archive.org/details/TheBattleOfElderbushGulch) is sometimes cited as an example of the contrary, bloodthirsty savage image of Indians. But their offense in the film is not that great. They try to eat a couple of dogs, hungry and not knowing this is taboo among whites, and are shot dead for it. A battle ensues.

Who here is being portrayed as bloodthirsty?

One might expect that a film called “The Indian Wars Refought,” filmed with the cooperation of the US government, might offer a more balanced account, if not an outright tribute to the US Army.

We will never know. The film was suppressed, claims Wikipedia, by the US government, and all copies disappeared. Reputedly, this was because it turned out to be too awkwardly pro-Indian and anti-US government, during a period of wartime censorship (IMDB; Larry Langman, Larry, American Film Cycles: The Silent Era. Greenwood Publishing Group [1998]).

In 1922, Canada produced what is commonly cited as the first ever feature-length documentary film. That would be “Nanook of the North,” a sympathetic portrayal of the life of an Inuit hunter. Roger Ebert calls it “alone in its stark regard for the courage and ingenuity of its heroes" (Ebert, Roger [2005-09-25] "Nanook of the North [1922]," Chicago Sun Times). Another “revisionist” view of aboriginal Canada; as they all are.

“They Died With Their Boots On,” 1941, again tells the story of the Indian Wars, culminating in the Battle of Little Big Horn. But, again, white men are clearly blamed: “The battle against Chief Crazy Horse is portrayed as a crooked deal between politicians and a corporation that wants the land Custer promised to the Indians.” “A letter left behind by Custer, now considered his dying declaration, names the culprits and absolves the Native Americans of all responsibility; Custer has won his final campaign.” (Wikipedia) It has to be so; if the Indians were guilty of anything, it would not be a satisfactory ending in the eyes of an American audience.

Of course, many may argue that this is simply telling it like it was—that the whites are fully responsible for the Indian wars, fought to take the Indian land. But was this true? Indians, after all, were always fighting one another. Why would they always make an exception of the white men?

“Sitting Bull,” 1954, was the first Western in CinemaScope. Again it was filmed from the Indian point of view. “When the white man wins,” the cinematic Sitting Bull complains, “you call it a victory; when the Indian wins, you call it a massacre.” This seems the eternal lament of the Hollywood Indian; but there never seems to have been a prior time during which everyone called the one a victory, or the other a massacre. It is simply part of the Noble Savage myth.

And then we had “Little Big Man”…

It is always possible, I suppose, that some day, someone actually will make an anti-Indian movie. Or write an anti-Indian novel.

But nobody will buy it.